About 300 years ago on November 23, 1746 Russian researcher and naturalist of German parentage Georg Wilhelm Steller died. He took part in the famous Second Kamchatka Expedition, which discovered a way to North America for the Russian Empire. On their way back packet boat St. Peter, with G. Steller on board, was cast away on reefs near an uninhabited island, which would later be named after Vitus Bering. The crew landed on the island and had to stay there for about a year, as they were rebuilding the ship and tried to survive in harsh conditions. Despite of the situation, Georg Wilhelm Steller never gave up on science, to which he was devoted throughout all his life. To honor the memory of this great researcher, we talked to Natalia Tatarenkova, Head of the Cultural and Historical Values Preservation Department of the Commander Islands Nature and Biosphere Reserve.

-

I would like to start with a general question: how did Georg Wilhelm Steller contribute to exploration and research of the Commander Islands?

-

In fact, he took little part in the exploration of the islands. The process was unstoppable even without his activity. For centuries the locals had known about some uninhabited islands near Kamchatka. Before the famous expedition there were Siberian Cossacks, who tried to reach the islands. But they were not destined to be the first to land there. In the 18th century simple uneducated people harnessed natural resources, such as the Cossacks, hunters or peasants. They had vast experience in surviving in extreme conditions. They didn’t need Steller’s science, but he desperately absorbed their knowledge in Siberia and on Kamchatka. So we can say, that Piotr Verhoturov, one of the crewmen of St. Peter packet boat and a Cossack, made a better contribution by telling the people of Kamchatka about lots of fur-bearing animals and by taking part in the first trade group in 1743.

On the other hand, Steller’s contribution to science is difficult to overestimate. He was the first to describe scientifically distinctive features and behavior of the sea lion, northern fur seal and many other animals. He made fantastic botanical and zoological collections. His botanical collection for Bering Island had 218 species, 51 of which he classified as new or little known.

-

There is a story that Steller and other crewmen of St. Peter packet boat survived by eating laminaria, which was Steller’s idea. Is it true?

-

Only people, who have a vague idea of the wintering place and who is unfamiliar with G. Steller’s Journal of the Voyage, can tell such stories. The fullest version of the Journal with thorough comments of Andrey Stanyukovich was published in 1995. Today it is accessible for everyone.

The most popular meal during the first days of their stay on the island was partridge soup. G. Steller recommended this soup to his siriously ill captain-commander. Together with several winged birds he passed to the ship several autumn stems of speedwell and supposedly scurvy grass to cook a salad of. These herbs are far from having delicate taste, but they are a nice remedy for Barlow’s disease. Other food found in the first days was ringed seal meat, later sea lion fat, which “tastes like beef marrow”, sea lion meat, which “tastes like veal”, and later on sea cow.

In the beginning of spring Steller started to collect edible roots and later fresh shoots. He collected plans himself and told the crew how to do it. He searched for cow parsnip and ligusticum and tubers of fritillaria. He also used stems of lungwort, rosebay, hemlock parsley, bitter cress and tubers of alpine knotweed. Instead of tea they used herbal infusion made of redberry, pyrola and speedwell leaves. Laminaria is mentioned only as food of sea cow.

-

It seems that Steller was idealized. Are there any stories, which show his real biography?

-

I think, that professor Johann Georg Gmelin gave a full characteristic of Steller: “… He had not many clothes… He had one vessel for beer, honey and vodka. He had no need in wine. He had one piece of plate to eat from and to cook in and never needed cook’s service. …He never wore wigs or powder and every shoe fitted his feet. …He could easily spend a day without eating or drinking anything, if he could contribute to the science.”

The most fascinating fact about these words is not actually its accuracy, but its tact. It is well known, that Steller wasn’t prone to compromises and was very hot tempered. In 1739-1740 he was doing a research in Transbaikal region, where he quarreled with J. Gmelin. The two opponents even issued complaints and accusations to Irkutsk Administrative Office and Academy of Fine Arts and Science. Gmelin asked the authority to ban Steller from going to Kamchatka…

In Russia we have a tradition to speak good of the dead or nothing at all. If someone wants to know about his day-to-day petty troubles, they may imagine it or - even better – read the scientist’s journal and published notes of Sven Vaxel. Besides, I would recommend reading Stelleriana in Russia edited by Eduard Kolchinsky. The most meticulous of us may want to dig into archives of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, as Letters and Documents of Steller were published separately in 1998.

-

Georg Wilhelm Steller died on the way back from Kamchatka through Siberia. Arbitrary rule played a role in his death. Have the situation changed a lot? What blocks the way of modern researchers today?

-

It is true, that in the 18th century there were no planes to take you from Kamchatka to St. Petersburg, so they had to cross our immense Siberia. But I wouldn’t compare arbitrary rule to some clumsiness of bureaucracy. Moreover, history was “seasoned” with intrigue, which was a usual companion of the discoverers.

After his marine expedition Steller spent two years on Kamchatka peninsular exploring its nature and local people. Once his actions led to an open conflict with local authorities. On his own initiative he gave permission to several locals to go home, though they had been formally arrested, but were neither guarded nor fed. Steller was accused of everything up to sabotage. On his way to St. Petersburg in Irkutsk he was arrested. Investigation proved him innocent, but later he was arrested again in Solikamsk. Some say, that Tobolsk governor Alexey Sukharev ight have been responsible for this. He allegedly suspended documents about Steller’s innocence, which should have been sent to Senate. So because of governor’s whim Steller had to return to Siberia. In Tara he met a messenger from St. Petersburg with an order to release Steller from arrest… That is how Steller found himself in Tyumen, where he died.

What blocks the way of modern researchers today? The same as thousands years ago: envy, stupidity and ignorance. Even now there are filthy lies about Steller’s death: “… on an uncommonly cold day the guard stopped in one of the taverns by the side of the road to have some vodka.” Today it is hard to say for sure, who needed to palter with facts and make a freezing drunkard out of Steller, who actually died in the house of an expeditionary healer Theodore Lau, which is a scientifically proved fact. It is known, that Steller was incurable and managed to draw up his will.

-

What Georg Steller could have taught modern scientists?

-

Steller devoted his whole life to science. I do not believe, that it is something one can be taught to do. And I doubt, that many would have wanted to follow his path – a life of a hermit full of hardships and misunderstanding is not an enviable destiny. One should be born with it. It is fortune and heavy cross, which can be carried by very few.

***

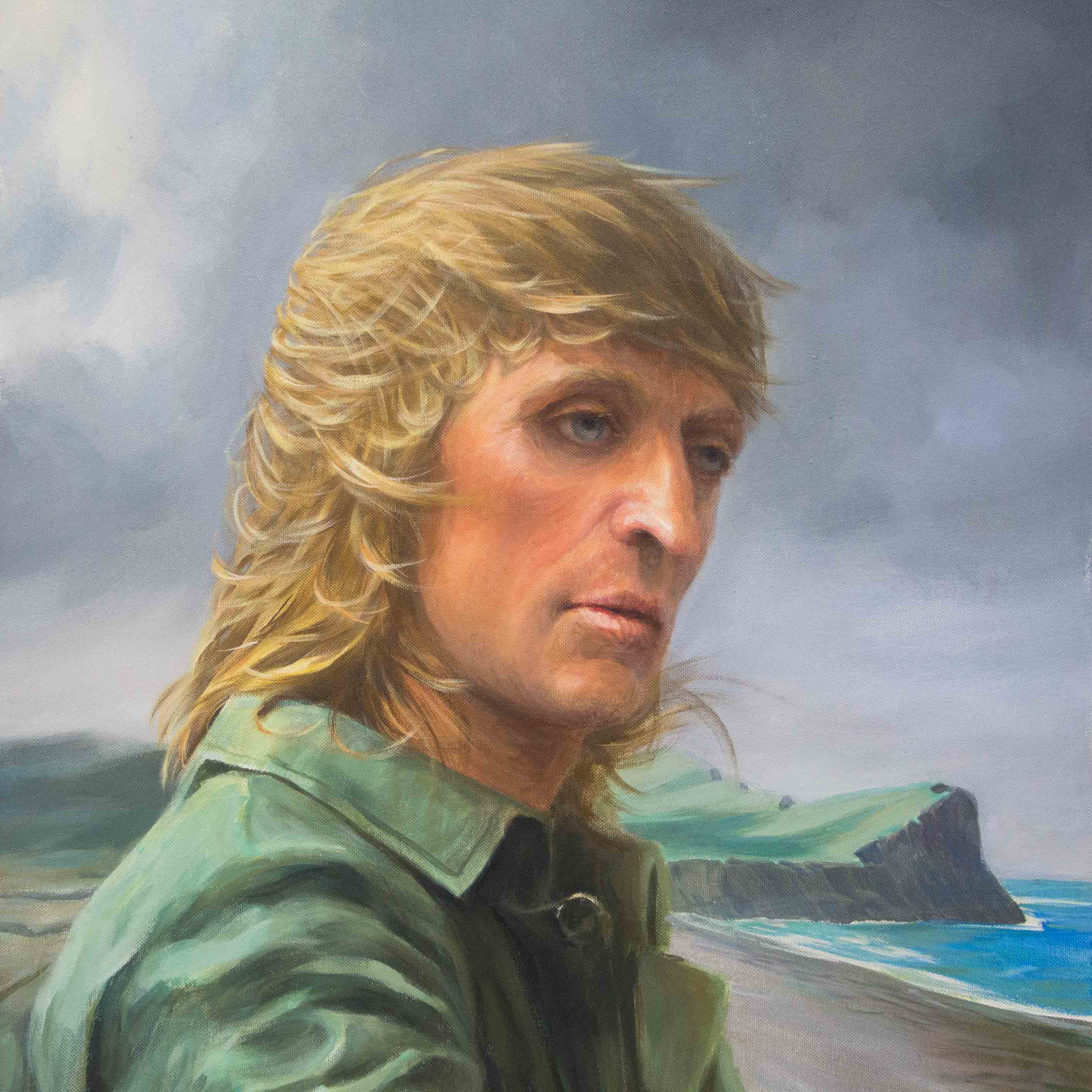

Illustration above is Georg Wilhelm Steller’s portrait by Denis Lopatin.

Interview is based on Natalia Tatarenkova’s article The Mystery of Russian Paganel, published in the 5th issue of Diverse Kamchatka journal in 2016.