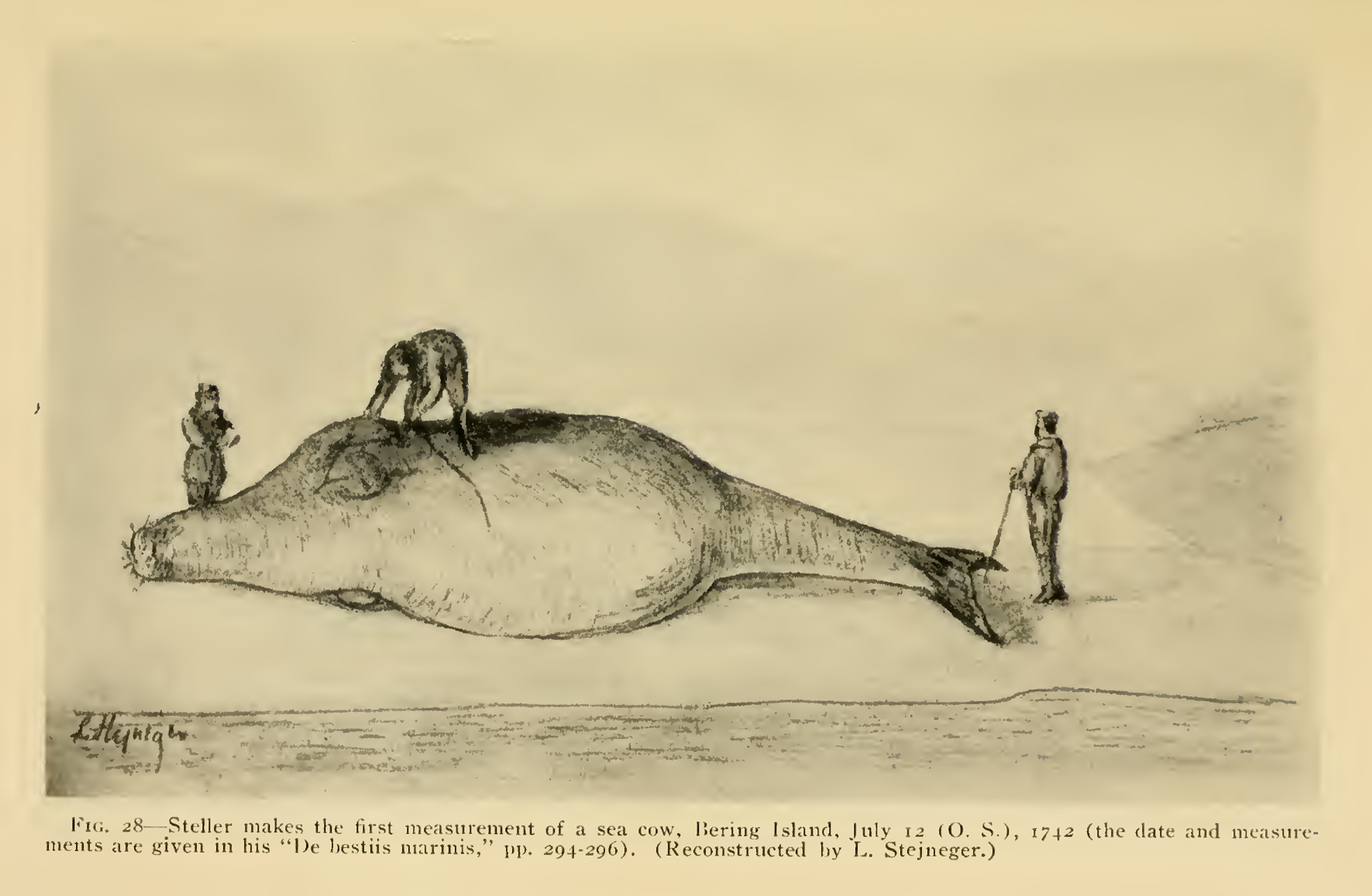

The first Europeans to hunt sea cows were members of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, headed by V.Bering. The exhausted team did not immediately start hunting this large animal. The first attempt took place only on May 21, 1742 and was unsuccessful, the boat was damaged, and they tried to hook the animal from the shore.

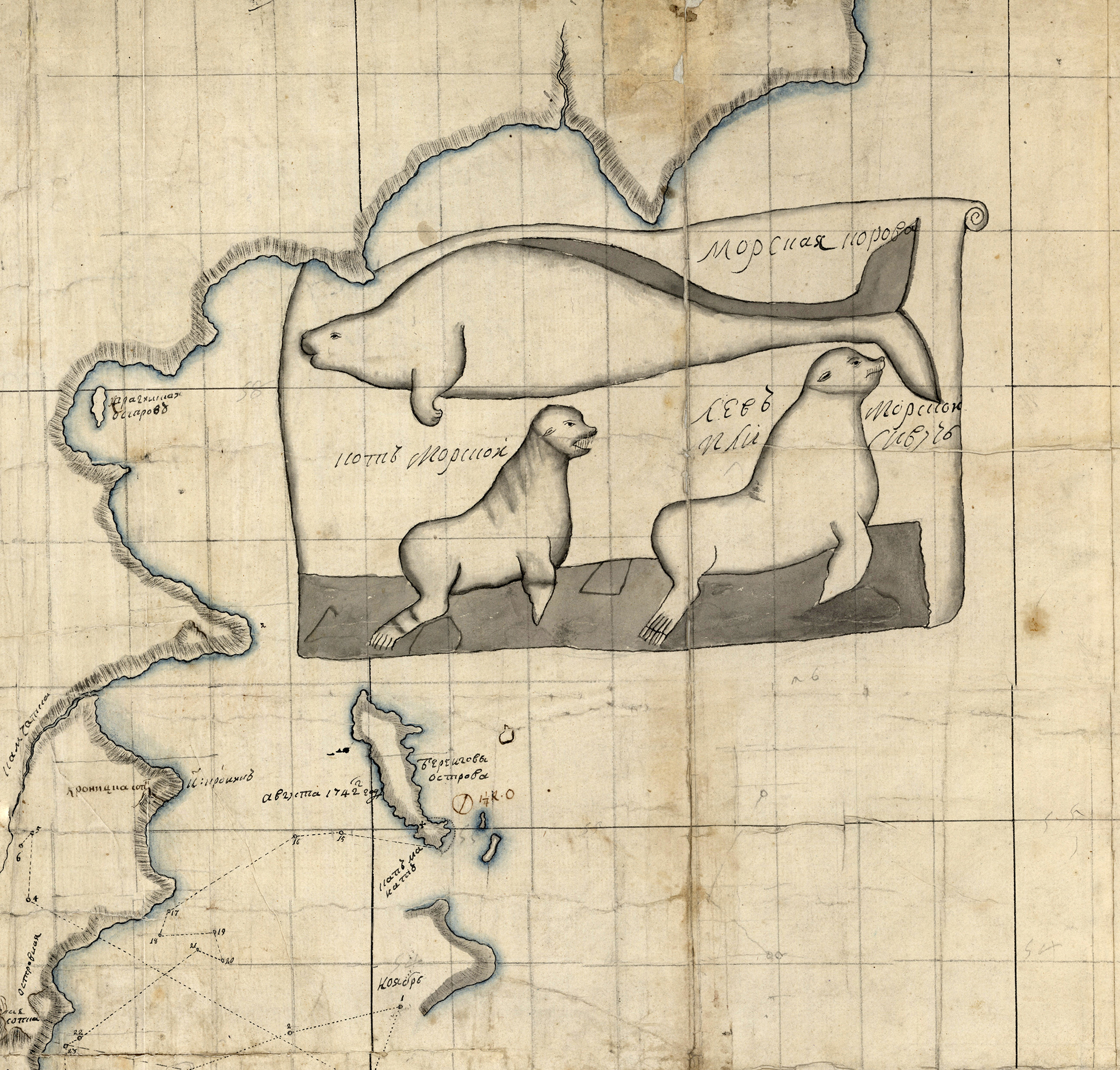

Fragment of a map based on campaign materials of the Second Kamchatka Expedition to the American shore in 1741–1742. Compiled by S. Vaksel and S. Khitrov in 1744 (RGAVMF.F. 1331.Op. 4.D. 79)

Only in June, when the long boat, which had been broken in autumn, was repaired, their efforts were crowned with success. The hunt was carried out according to the principle of whale hunting - the animal was harpooned by approaching it closely on a longboat, and then pulled to land with a rope attached to the harpoon. During this time, the longboat's team drove bayonets into different parts of the body to make the animal lose as much blood as possible. The carcass was dragged ashore at high tide. Then they dressed the carcass. They used exclusively meat and fat - for food:“Its meat is extremely nutritious. I can say that none of us would have recovered from scurvy if we had not started eating the meat of this animal ", - recalled S. Waxel. No evidence of the use of the skin (especially since it was severely damaged during the described hunting method), bones or fat for other uses has not been stated.

Russian industrialists who regularly visited the Commander Islands from the middle of the 18th century were more practical [1] . Meat and fat were still used for food -"that one cow of meat was enough with leftovers to all 33 people for one month"- and was harvested for future use in salted and dried form for trips to the east. The fat was used to keep the fire in the lamps (zhirniki), and the skin was used instead of the planking boards of the boat set. Industrial hunters, going on a campaign, chose a good large light larch tree on Kamchatka, made a boat keel, ribs and the entire stern and bow set for one or two boats from it, and took it with them on the campaign. In addition, they assembled one ordinary dinghy with full wood sheathing for the Commander Islands.

On the Commanders, during the wintering period, the skins of the sea cow were harvested in abundance. The skins were called laftaks - as were the roughly dressed skins of sea lion, fur seal and eared seals, along with cow skins, which served to cover boats and canoes. They took folded laftaks and prefabricated boat parts with them on ships and assembled on the spot when the need arose. The leather was soaked in water and covered with a wooden frame. Such boats were more convenient to handle: they were stable on the water, which is especially important in conditions of a constant strong run-up during disembarkation and launching. They had a shallow draft, high carrying capacity and were very light. In order to move the leather boat overland over a considerable distance, the effort of only four men was enough to pull it ashore - even less (it was necessary to pull the boats out every time to protect them from bow waves). The Russians used these leather kayaks in the Aleutian manner as a temporary shelter or a tent. In addition to covering the boat, the skin of a sea cow was used to make soles for torbases (soft boots made of leather). They liked to eat fresh kidneys raw.

Since the late 1740s (early 1750s), they began to hunt the cow with a "pokolyga” - a sword strip attached to a pole or its analogue of “five quarters” (90 cm) in length. They struck a blow "against the front legs" from a distance of "two printed fathoms" (about 4 m). Then the dinghy or canoe quickly moved aside and chased the animal from a distance. When the cow was exhausted, she was harpooned with six vershoks (26.7 cm) long iron "toes". A rope with a length of about 50 fathoms (107 m) was attached to them. When the animal "fell asleep", it was pulled to the shore. This hunting method was within the power of a group of 8-10 people.

A written evidence of commercial hunting for a sea cow for the purpose of harvesting laftaks was made by the navigator of the "Holy Trinity" Ivan Korovin (campaign 1762-1765). The vessel was hunting on Bering Island from October 8, 1762 to August 1, 1763 (Julian).

In addition to the rational methods of hunting described above, “harmful” ones were practiced. A description of such a hunt was given by the surveyor Yakovlev, who spent the winter on Bering Island in 1754: “When industrialists come to hunt, we see them in small batches of two and three. They live all over the northern commander's island [Bering Island] shore in different places, <...> and they have nothing but cow meat; then they cause those herds of cows <...> a huge waste and death, as a person from the shore or shallowly enters the sea and stabs the aforementioned with pokolyga, tying it to a long pole and wounds one or the other cow mortally; but those wounded cows go into the sea, and there, when they are exhausted from the wounds, the sea does not quickly sweep their meat to the shore, and after a long time after stabbing, each cow, if not dressed, becomes sour and is unfit for food. " Yakovlev accused the workers of Trapeznikov's company who hunted on the island of the predatory method of hunt on Bering Island on the ships Abraham and Nikolay.

The Last Cow

Hooker boat St. Peter of the Second Kamchatka Expedition was not the only vessel rebuilt on Bering Island. In 1752, St. Boris and Gleb campaign of Nikifor Trapeznikov came to the island, but the rope of the only anchor was torn off, and the schitik was thrown ashore and smashed. Over the course of two winters, the team has been collecting the lumber and building a new ship - St. Abraham schitik. <…> July 24, 1866 "Abraham" led by navigator's apprentice Vasily Sofyin [2] went to sea and a few days later approached Medny Island. Here the schitik "touched the ground" and was damaged. At first, they wanted to lift it ashore and fix it, but they abandoned this venture due to the lack of forest for the slopes and difficult terrain. Sсhitik was completely dismantled and in two years a new ship was built - St. Peter and Paul. The main group worked on Medny Island, and 14 people went on canoe to Bering Island. They set off on the way back on July 29, 1768: they took comrades from Bering Island, and then headed for Kamchatka. There is no doubt that these days the team crossed paths with the expedition of Levashov and Krenitsyn.

On May 4, 1764, a decree of Empress Catherine II was issued on the organization of a secret expedition led by Pyotr Kuzmich Krenitsyn. Mikhail Dmitrievich Levashov became Krenitsyn's assistant and the commander of the second ship. On July 23, 1768 St. Catherine galliot under the command of Captain 2nd Rank Krenitsyn and St. Paul hooker boat under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Levashov left the mouth of Kamchatka and on July 27/28 they approached the southwestern coast of the Commander Island, or Bering Island. The expedition ships proceeded along the southwestern coast of Bering Island and passed through the strait between the islands. On July 29/30 Levashov's St. Paul and Sofyin's St. Peter and Pavel were at a point opposite Cape Manati. Shortly before this meeting, members of the naval squadron witnessed the industrialists of the Bering Island team to have killed the "last" sea cow.

According to the official version, the members of the government expedition of 1764–1770. were witnesses who saw the industrialists harvest the last sea cow. Most likely, the carcass was dressed not far from the present Nikolskoye Village.

However, in the family of the Bering Creoles the Burdukovskys, there was a legend that their grandfather Vasily Burdukovsky (robinson in the brigade of Fyodor Shipitsyn) saw a sea cow in his youth. We are talking about the beginning of the 1770s: not earlier than 1770 and not later than 1773. During this interval, 5 different campaigns hunted on the Commander Islands.

According to a family legend, when Vasily was 18 years old,“they still hunted sea cows”,ate the kidneys and knew how to thin leather to such a state that they could make a skin for a canoe out of it. Is it true? - it is not excluded, since for 5 years after the official date of extinction, single individuals could still occur.

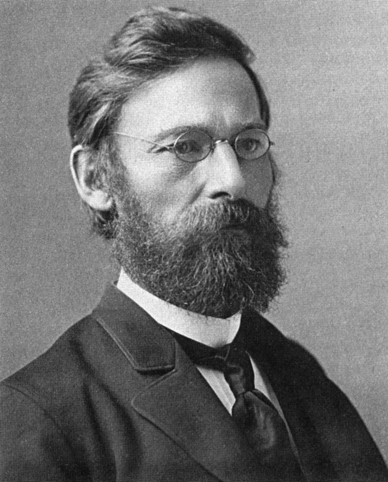

This story seamed believable to the head of the expedition around Eurasia Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiold on the sail-steam barque Vega. During the time until August 1879 Vega stood in front of the modern Nikolskoye Village (then it was called Gavansky), Nordenskiold conducted a survey of the local population including the son of Vasily, Peter Burdukovsky, as well as the Creoles Fyodor Mershenin and Nikanor Stepnov. The latter two claimed that a quarter of a century ago they saw a strange animal in the area between Cape Tolsty and Kislaya Bay. Nordenskiold suggested that it might be a sea cow and changed the extinction date to 1854.

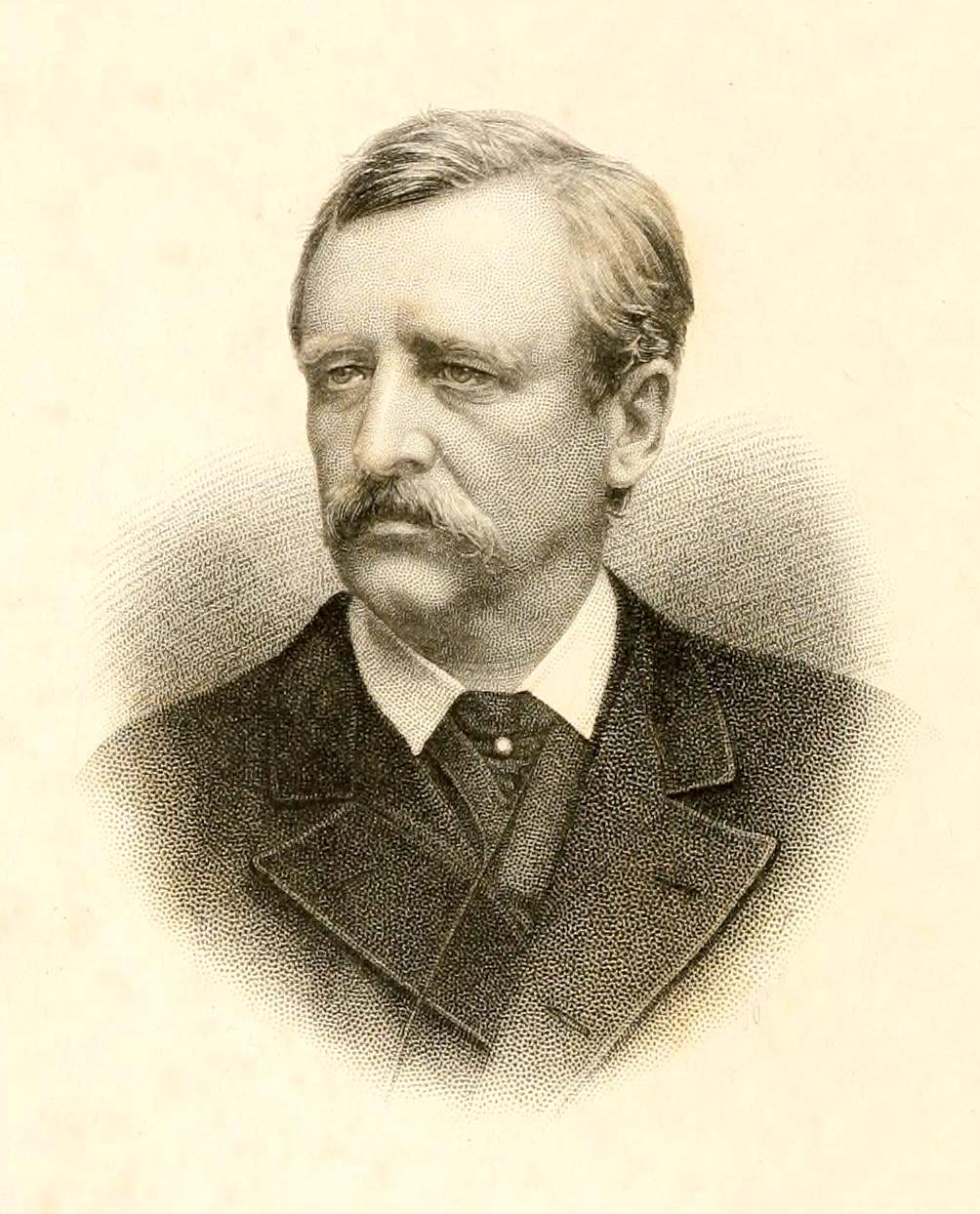

Adolf Nordenskiold

American zoologist Leonhard Stejneger was skeptical about Nordenskiold's statement. In 1882, he conducted his own investigation and interviewed Stepnov and Mershenin in the presence of an agent of the trading house Yegor Yegorovich Chernykh, so that he could attest to the correctness of the record and the correctness of the survey. As a result, it turned out that approximately in 1854, the villagers saw not a sea cow, but some kind of a "floater". In those years they called "floaters" not only the floaters themselves, but also the beaked whales.

Thus, the date of extinction remained the same - 1768 with the proviso that single specimens could occur for several more years.

Finding the bones of an extinct animal

The species Hydrodamalis gigasceased to exist, but the locals of the Commander Islands used the bones of this animal for a long time. In the 19th century, they were actively used, especially the ribs. They acted as a substitute for wood and partly for iron, as a hard and durable, but more brittle material. Fragments of bone sled skids can still be found in the places of hunting settlements. Dog sleds existed only on Bering Island, the rocky Medny Island is not suitable for such transport. Local sleds were used to ride the damp valleys and slopes at any time of the year, so they had to be very strong. To achieve this, wooden runners were upholstered with bone plates (sub-runners) cut from the ribs. In the 20th century, bone was replaced with iron.

Residents often used bone wedges to split driftwood, bone plates, and even something of a bone bar. The weighting nozzles of the Aleutian "arrows" were also cut out of the ribs of a sea cow. A variety of household utensils was made of bone: beaters, diggers for fritillary bulbs and other plants, neadles for weaving nets, handles for household tools, needle cases, buttons, mouthpieces (a collection of such items is kept in the Aleutian Museum of Local Lore).

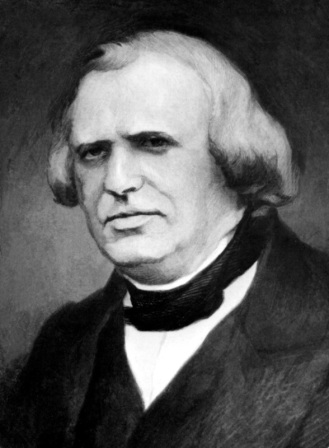

In the summer of 1844, anaomist of Zoological museum I.G. Voznesensky made the first scientific collection of the bones - the Academy of Sciences sent him to the Far East specifically to replenish the collections. Ilya Gavrilovich stayed on Bering Island for only 48 hours, but during this time he was lucky enough to unearth vertebrae and two skulls of a sea cow on the seashore: incomplete and a whole one.

Ilya Gavrilovich Voznesensky

In 1875, Karl Neumann, the ruler of the East Siberian Department of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, removed fragments of two skulls, vertebrae, ribs and part of a scapula from the territory of the northeastern part of the island. The preservation of the bones led him to the conclusion that"the remains found do not contradict the opinion of the extinct state of this animal".

Nordenskiold preferred not to waste time searching and bought bones from the Aleuts. The collection took up 21 large barrels! Since 1877, the zoological collections have been replenished by the efforts of Nikolai Grebnitsky, the manager of the Commander Islands, Candidate of Natural Sciences. He explained to the Aleuts the importance of the finds, and they began to actively search for valuable specimens. Several skeletons were found in 1879 alone: Stepnov found one behind Slastnaya, Sinitsyn - on Buyannovsky reef and Pakhomov - at the same place. The latter was preserved the best, 19 feet (5.8 m) long, with some caudal vertebrae missing. Do you think the Aleuts handed over samples to the manager and he profited from it? - not at all. Grebnitsky only controlled the correctness of the finds. Residents sold their finds themselves.

In 1882-1883. the collection of bones was collected by Leonhard Stejneger. The collection went to the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, D.C.). Skeleton purchased in 1879-1883 Benedict Dybowski, was first taken to Lviv, and later transferred to the Museum of Natural History of Vienna (Austria). Some of the bones remained in Lviv. And so on.

Vienna, 2011

More recently, the Italian zoologist Stefano Mattioli raised a huge array of records and tracked the movement of bone remains of Hydrodamalis gigas. Its co-author in a 2006 publication was American zoologist Daril Domning, a recognized specialist in the Siren order.

Sea cow in Island Place Names

Looking through the place names, the uninitiated viewer will not see a single one connected to the Steller sea cow. How can it be so? After all, the sea cow is in a sense a symbol, a name card of the Commander Islands. In fact, two objects are dedicated to this amazing animal - a cape and a stream.

The Russian outdated name for Sirens (sea cows) is "manati", in Latin it isManatus. In the south of Bering Island there is Cape Manati, or Monati (modern misspelled version). This name was given in 1742 by the crew of the St. Peter hooker boat. Originally it sounded like Kap Manat.

Between rivers Fedoskaya and Kamenka, south of river Peschanka, the Trifonovsky stream flows. This toponym is also associated with the sea cow, but indirectly. It commemorates the name of Trifon Sinitsyn. Trifon Ivanovich (about 1844-1918, great-grandfather of the Sinitsyns-seniors) was a well-known person. He became famous for his unique finds of sea cow bones. He sold the first skeleton (without the tail) to the Zoological Museum of St. Petersburg. In 1884 Sinitsyn received a medal for this find. Together with him, Nikanor Petrovich Galkin (1831-1894, great-great-grandfather of Gennady Ignatievich Badayev) was awarded“for their tireless labors and diligence, which they show in the search of the sea cow (Rhytina Stelleri) remains for the Zoological Museum of the Academy of Sciences, whole skeletons which are now very rare ". In May 1891, on the southwestern coast near Cape Tonky, Trifon found a complete skeleton for the first time; it was sold to Barton Everman. The skeletons and their fragments collected by Sinitsyn are kept in different museums around the world: in St. Petersburg, Washington, Edinburgh and Lviv.

[1] This statement hardly applies to the first campaigns of E. Basov - cows were caught with a hook, but boats were not covered with skin.

[2] Among other things, Sofyin at Levashov's request made a map of the Commander Islands.

Author: Natalya Aleksandrovna Tatarenkova, Head of Historical and Cultural Heritage Preservation Department of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "State Natural Biosphere Reserve" Komandorsky "named after S.V. Marakov.

Literature

- Mattioli S., Domning DPAn annotated list of extant skeletal material of Steller's sea cow (Hydromalis gigas) (Sirenia: Dugongidae) from the Commander Islands // Aquatic Mammals. -Vol. 32 (3), 2006.

- Nordenskiold A.E. The voyage of the Vega round Asia and Europe. - NewYork, 1882.

- Stejneger L. Investigations relating to the date of the extermination of Steller's sea-cow // Proc. of the U.S. National Museum. -Vol. 7, 1884. - Washington, 1885.

- Vaksmut N.S.A note on the skeleton of a sea cow (Manatus Stelleri - Stellerus borealis) // "Priamurskie vedomosti": weekly. No. 278 dated April 25, 1899.

- Tatarenkova N.A.On the use of meat, fat, skin and bones of the sea cow(Hydrodamalisgigas)// Conservation of the biodiversity of Kamchatka and adjacent seas. Proceedings of the international scientific conference. - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 2006. URL: http://www.terrakamchatka.ru/conf2006.php URL: http://www.terrakamchatka.ru/conf2006.php

- Tatarenkova N.A.Methods of hunting sea cows(Hydrodamalisgigas)and one of the reasons for its rapid extinction // Conservation of biodiversity of Kamchatka and adjacent seas. Proceedings of the international scientific conference. - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 2006. URL: http://www.terrakamchatka.ru/conf2006.php

- Tatarenkova N.A.Toponyms of the Commander Islands. Moscow, 2018. URL: http://www.biodiversity.ru/publications/books/regions/Tatarenkova_Toponyms_2018_web.pdf